At the beginning of the 20th century, amidst the rolling hills of the Battle River Valley in central Alberta, the town of Ponoka was thriving and preparing for a bright future. On one of these hills, the Centennial Centre was constructed as Alberta’s first mental health hospital, originally named the Provincial Mental Hospital. A constant flow of horse-drawn wagons carrying workers, equipment, and building materials connected the community to the hospital’s construction site. Read more about its story on icalgary.

Early History

In 1905, when Alberta became a province, there was a growing need for public services. Visionary politicians identified the absence of a facility dedicated to the care and treatment of individuals with mental health issues. At the time, patients were sent as far as Manitoba, which was a lengthy and challenging process.

In 1907, Alberta passed the Insanity Act, which regulated care for the mentally ill and detailed how their estates should be managed.

Dr. W. A. Campbell from Ponoka was sent to Edmonton to advocate for the economic benefits of building a psychiatric hospital in Ponoka. He emphasized the long-term economic advantages of hosting a permanent medical facility staffed by professionals who would establish homes in the community.

Edmonton approved the plan, and in 1908, Alberta’s Premier Alexander Rutherford officially decided that the hospital would be built between Calgary and Edmonton in Ponoka.

Construction

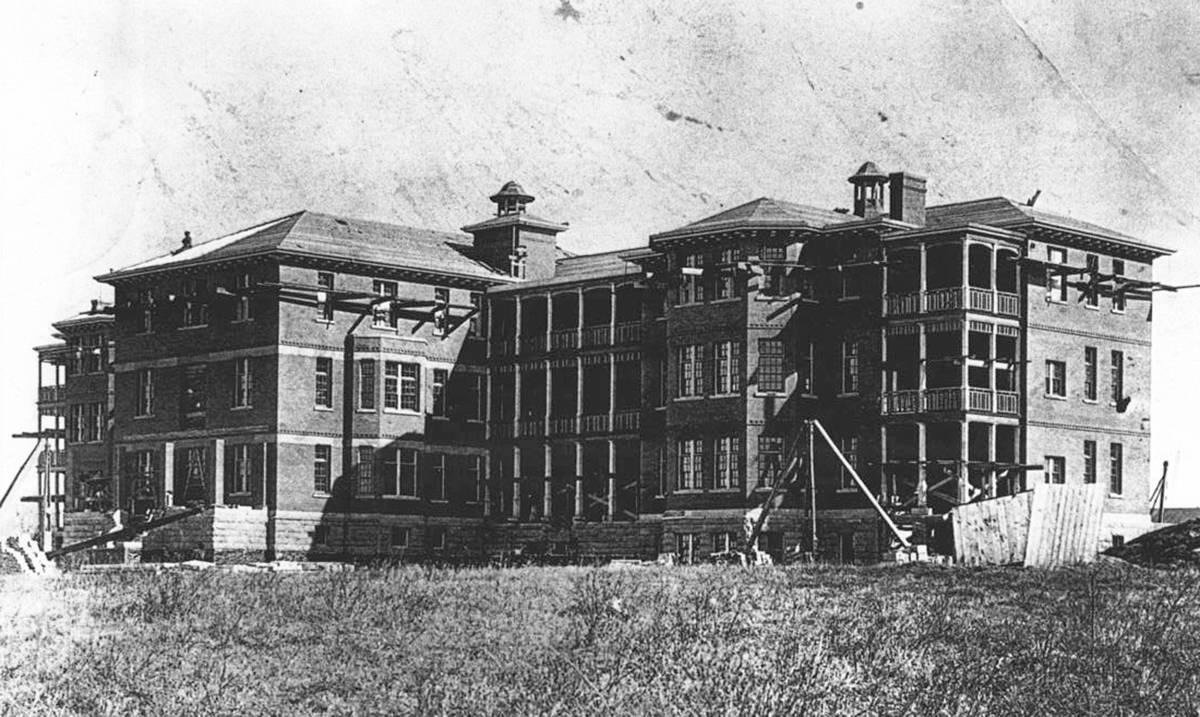

The hospital was hailed as a symbol of progress in Alberta. Designed by architect A. M. Jeffers and modeled after a hospital in Utica, New York, it was a monumental project.

J. W. O’Brien and his son Ernie, alongside others, transported heavy materials and equipment from the bustling Canadian Pacific Railway line in Ponoka to the site. While some large items were lifted by crane, most materials were manually unloaded by hardy workers.

The ground at the construction site was unsuitable for a stable foundation, so wooden pilings were sunk 25 feet deep. Cement production required tons of rock, which was crushed using over 20 steam crushers and mixers. A 200-foot well was drilled near the future power plant, which became a crucial part of the hospital’s infrastructure.

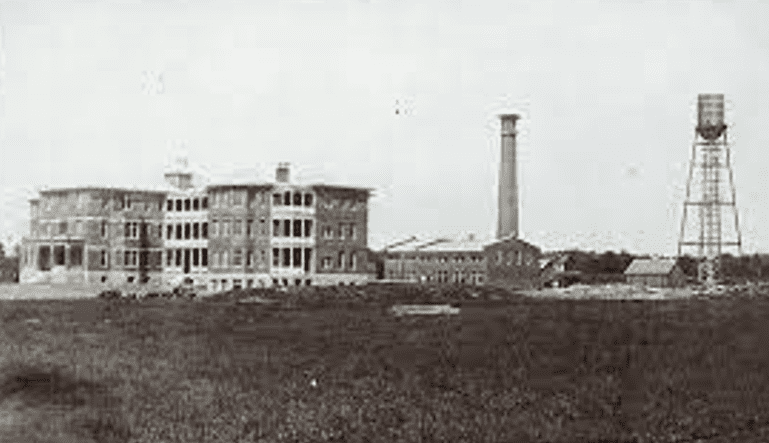

The power plant was connected to the main hospital building through an underground tunnel. It generated high-pressure steam that powered an electrical generator, which provided hot water for the laundry, kitchen, and plumbing system while maintaining warmth throughout the hospital.

The central brick administrative building (later known as the Heritage Building) was three stories tall, 139 feet long, and 45 feet wide. It housed medical, administrative, and support staff and had two patient wings. The basement was used for storing equipment. Designed to accommodate 150 patients, it featured additional wings with dormitories, working rooms, spacious lounges, verandas, and day areas with fireplaces.

The hospital took three years to build. During this time, workers lived in tents or shared small homes, while a few resided in Ponoka’s boarding houses. Payday weekends brought the workers into Ponoka to patronize local pubs and shops. They also enjoyed swimming in the Battle River, playing baseball, or hockey. Frank Young, who managed the hospital for over 30 years, recalled organizing sports teams for the workers during his teenage years.

The hospital was built with fire-resistant materials like stone, brick, steel, concrete, and terracotta blocks. It featured state-of-the-art heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. The facility was fully equipped with electric lighting, fire alarms, and advanced plumbing.

The isolated power plant produced enough electricity to light the hospital and surrounding grounds, operate the elevator, and power laundry and plumbing equipment. Until 1929, it even provided electricity to the entire town of Ponoka.

The Centennial Centre was completed in the fall of 1910. Alongside the hospital and power plant, an 80,000-gallon water tower was built, supplied by the nearby well.

Opening

Staff were recruited from across Canada and the U.S. The hospital officially opened on July 4, 1911. All mentally ill patients from Alberta, who were previously treated in Manitoba, were transferred to the new facility. At the same time, Alberta formally recognized the role of medical practitioners in mental health care.

Dr. T. Dawson was appointed as the hospital’s first medical superintendent. He was impressed by the facility’s luxurious and comfortable environment, which prioritized patient well-being. Decorative electric lamps dispelled the gloom typically associated with psychiatric hospitals. The hospital was also equipped with a rare telephone system.

The patient rooms resembled ordinary bedrooms without restrictive barriers. From its first day, the hospital was filled with patients, and staff began implementing progressive care and treatment programs.

Services Provided

The Centennial Centre offers treatment and support for individuals experiencing mental health crises and brain injuries. It provides care for patients with mood disorders (such as anxiety), mental illnesses (including schizophrenia, delusional disorders, bipolar disorder, and depression), and dementia. Treatment methods include medication, behavioral and group therapy, proper nutrition, and healthy sleep routines.

In the early 21st century, feedback from patients and their families was mixed. On July 22, 2021, Alberta Health Minister Tyler Shandro visited the facility, stating that Alberta should be proud of the hospital. He remarked that its services were “a step above” other psychiatric facilities in the province.

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted the hospital to introduce a remote treatment program, enabling patients to live fulfilling lives despite mental health symptoms or addictions. The program offers online courses and sessions covering topics such as anxiety management, relapse prevention, peer support, interpersonal skills, and coping strategies.

However, the program is not a substitute for in-person care. Patients in crisis or those requiring treatment adjustments must still access inpatient services. The remote program is intended as a supplementary resource for those already receiving or having received care at the hospital.