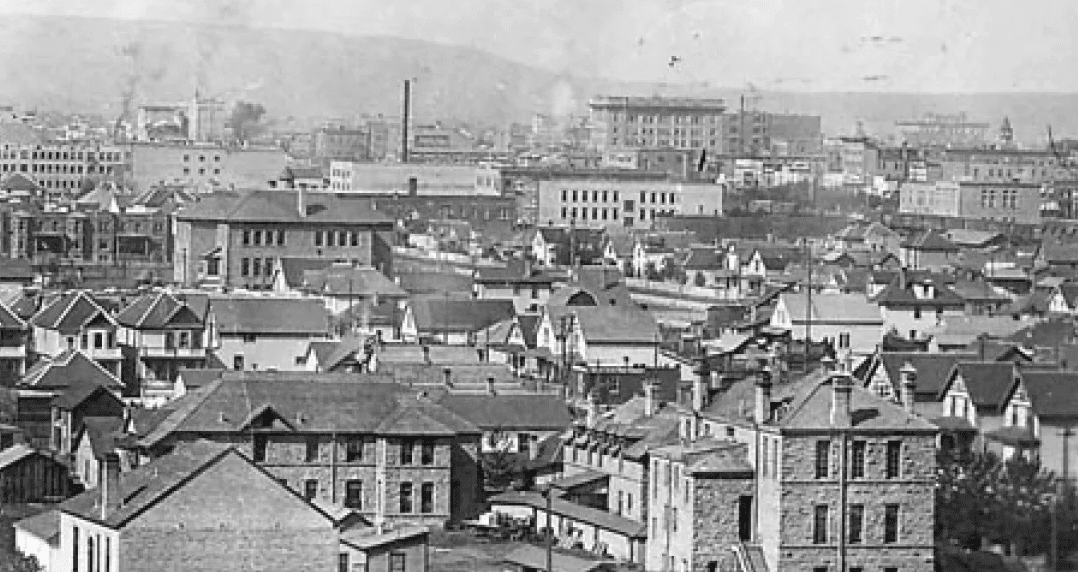

It is not always possible to pinpoint exactly when and how a pandemic affected a city, but the arrival of the “Spanish Flu” in Calgary in 1918 is well-documented. This allows us to observe some interesting parallels and learn from the mistakes of the past to better prevent the spread of similar diseases in the future, as reported by icalgary.

The Disease Brought by Soldiers

On October 2, 1918, at 3 a.m., Calgary soldiers arrived from the front lines at the Canadian Pacific Railway station, located where Calgary Tower now stands. A military escort awaited them.

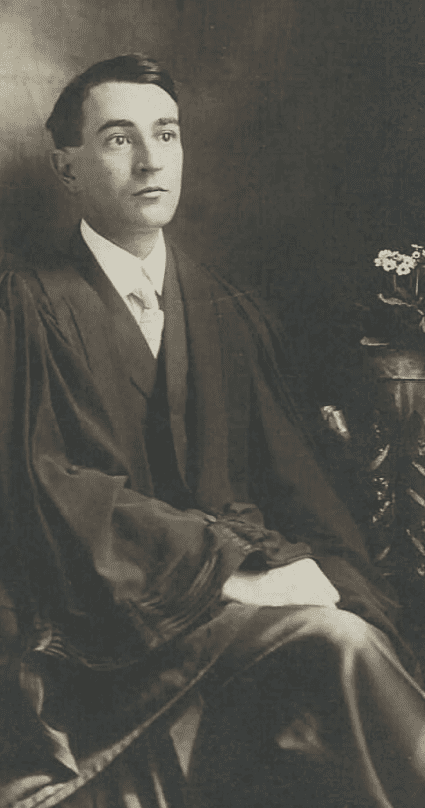

Calgary doctor Cecil Stanley Mahood had been informed that several men on board were infected. He escorted the soldiers to an isolation ward at the local hospital, the remnants of which are now known as the Rundle Ruins.

Dr. Mahood, originally from Huron County, Ontario, had trained and worked in Chicago and Denver before coming to Calgary. As the public health officer, his advice was widely respected. After the soldiers’ arrival, Mahood clearly explained to the public how the Spanish flu spread, emphasizing that it was transmitted through nasal, oral, and respiratory secretions. He advised avoiding crowded places and explained that every citizen was part of the mechanism that could slow the disease’s spread. While the soldiers recovered, other Calgarians contracted the flu.

The First Death and New Containment Measures

Many infected individuals developed pneumonia, which often proved fatal. The first death in Calgary from the “Spanish Flu” occurred on October 7, when Hazen Spearing died of pneumonia in isolation.

As the disease spread, a concerned Dr. Mahood ordered infected homes to be quarantined and cordoned off, even without official permission. Lawmakers later amended legislation to legalize his actions. In a bulletin dated October 12, Mahood urged caregivers to wear masks.

Despite warnings, large gatherings continued. A labor rally, a concert in the Palliser Hotel ballroom, and numerous Thanksgiving celebrations contributed to the outbreak. By the end of the week, Mahood declared the onset of an epidemic and called for social distancing. Schools, churches, cabarets, dance halls, billiard rooms, and theaters in Calgary and nearby areas were closed.

Mobilizing Medical Staff and Setting Up Hospitals

To address the shortage of medical personnel, school nurses and even teachers were recruited. Mahood converted the isolation hospital into an emergency hospital. When it became full, a temporary hospital was set up at the city’s technical college. Soldiers were treated at the Sarcee Camp military hospital near the present-day Westhills shopping center. Tents were added to expand hospital capacity, and Victoria School was turned into a recovery ward.

In 1918, finding personal protective equipment was a significant challenge. As masks became mandatory in public places, nurses mass-produced them at the Memorial Park Library and sold them to residents for 10 cents each. However, many Calgarians found the masks bulky, unattractive, and potentially dangerous if not changed regularly.

As the flu continued to spread, local healthcare workers faced relentless workloads. Some died, and Dr. Reginald Burton Dean, who worked alone for weeks at the school-turned-hospital, ultimately resigned.

Community Support

To assist those quarantined at home, women volunteers established makeshift kitchens in local schools. One such kitchen was Good Eats Cafe, while women from Calgary’s Jewish community opened a kosher kitchen in what later became the municipal complex, providing meals to those in need.

James (Cappy) Smart, Calgary’s fire chief from 1898 to 1933, coordinated volunteers and managed the schedules of vehicles transporting patients and nurses.

Resistance and Challenges

Some children were left without care as their parents became critically ill. Stanley Jones School was converted into a dormitory for these children, while orphans were sent to a shelter in Ogden, where matron Mildred Klint cared for dozens of children until her own death.

Not everyone adhered to sanitary regulations. Court records from the time list numerous individuals caught without masks, including doctors. Even Fire Chief Cappy Smart was caught, explaining that he could not give orders while wearing a mask.

The pandemic struck during a turbulent time. World War I was ending, municipal elections were underway, workers were striking, and schools were overcrowded. In October and early November 1918, thousands of residents fell ill, and many died. As the number of cases declined, some emergency hospitals were closed—an error in hindsight.

The Second Wave

After the signing of the Armistice of Compiègne on November 11, 1918, which ended World War I, Calgarians removed their masks and began celebrating.

As cases declined, Dr. Mahood believed the pandemic was over. Despite warning of a possible second wave, he agreed to lift restrictions. Theatres reopened on November 20, schools resumed on December 2, and municipal elections were held. Politicians began questioning the funds spent on hospitals and compensating nurses and volunteers.

The second wave began shortly after. Though it infected fewer people, it caused a higher mortality rate. Dr. John Albert Butterwick became the first Calgary physician to die from the Spanish flu, just days before his 36th birthday.

Stanley Jones School was again turned into a hospital, where medical staff worked 12-hour shifts. The pandemic began to subside in 1920.

Final Numbers

The Spanish flu claimed the lives of 384 Calgary residents (out of a population of 60,000) and 4,000 Albertans overall. It also took the lives of notable Calgarians, including athletes Robert J. Watt, Trevor Williams, and Edgar Walker; entrepreneur Susan H. Cartwright; and Alberta’s prominent woman, Euphemia (Effie) Bagnall.

The Spanish flu returned in smaller waves throughout the 1920s.

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from January 1918 to December 1920, infecting approximately 500 million people—about a quarter of the world’s population at the time. It caused an estimated 17 to 50 million deaths, with some sources suggesting up to 100 million.

The pandemic began near the end of World War I, but the exact number of early cases was often concealed to maintain morale. Military censorship was absent only in neutral Spain, where the true extent of the epidemic was reported. This led to the mistaken belief that Spain was the origin of the pandemic, hence the name “Spanish Flu.” Its exact geographical origin remains unknown.